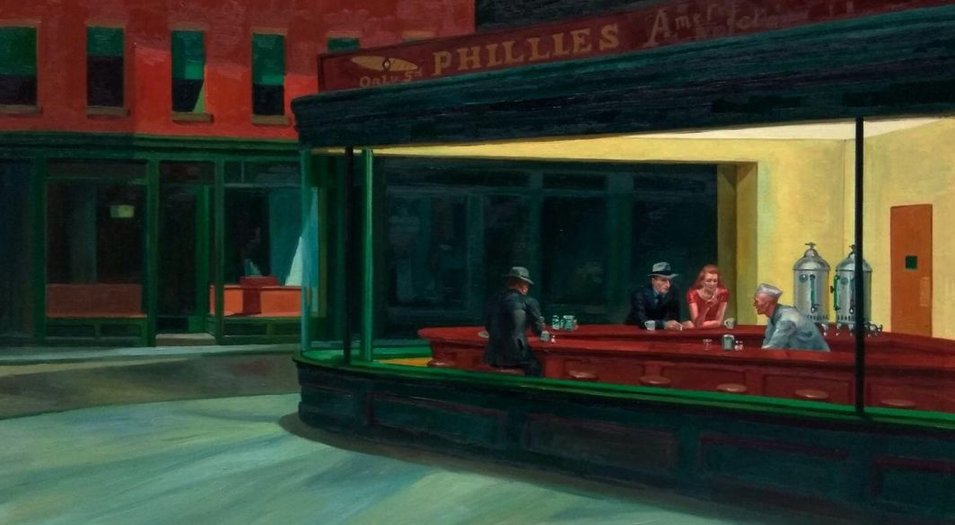

The activity of the man inside the counter gives us a kind of hope. Our eyes catch him first, but receive nothing in return. Other figure dark sinister back at left.”Īt the direct centre of the large canvas sits the ‘dark sinister’ figure, his back turned to us, unwilling or unable to communicate. Man night hawk (beak) in dark suit, steel grey hat, black band, blue shirt (clean) holding cigarette. Girl in red blouse, brown hair eating sandwich. In her notes on the painting, Hopper’s wife, Jo, describes them as such: “Very good looking blond boy in white (coat, cap) inside counter.

The painting’s strange silence is given force by the composition of the four people who occupy it. The detailed rendering of the empty shop across the street is a careful and potent observation of utter absence. It’s all sharp verticals and pronounced horizontals, frames and doorways, shadows and blockages. The architecture of the painting seems designed to compartmentalize, divide, separate. Hopper instead chooses to observe an oppressive silence, picking out the figures and their features in a way which suggests great, silent distances between them, despite sharing the same bubble of space and time. One might guess that a downtown diner would be alive with news, debate, and speculation at such a historic time. Nighthawks was completed in January of 1942, just weeks after the United States had joined the Second World War. But when reflecting on his most successful and evocative painting, even Hopper himself had to admit it: “Unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city.” He did not, he would insist, intentionally imbue his urban scenes with that unspoken pregnancy of human feeling, that eerie, uncommunicative atmosphere of the modern metropolis, with which they’ve become associated. (The red-haired woman was actually modeled by the artist’s wife, Jo.) Hopper denied that he purposefully infused this or any other of his paintings with symbols of human isolation and urban emptiness, but he acknowledged that in “Nighthawks” “unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city.In 1942, Edward Hopper painted his most well-known work, the powerful solitude of which regained relevance during the pandemic.Įver the evasive and guarded personality, Edward Hopper would often stringently deny the popular readings of his paintings. The four anonymous and uncommunicative night owls seem as separate and remote from the viewer as they are from one another.

Hopper eliminated any reference to an entrance, and the viewer, drawn to the light, is shut out from the scene by a seamless wedge of glass. Fluorescent lights had just come into use in the early 1940s, and the all-night diner emits an eerie glow, like a beacon on the dark street corner. Hopper’s understanding of the expressive possibilities of light playing on simplified shapes gives the painting its beauty.

One of the best-known images of twentieth-century art, the painting depicts an all-night diner in which three customers, all lost in their own thoughts, have congregated. Edward Hopper said that “Nighthawks” was inspired by “a restaurant on New York’s Greenwich Avenue where two streets meet,” but the image-with its carefully constructed composition and lack of narrative-has a timeless, universal quality that transcends its particular locale.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)